“He was born around 1744 in Tepeleni in Albania. At the age of nine, he was left fatherless and he was raised by his mother, Hamko.

By means of several intrigues, he eliminated his rivals and in 1784 he was made in charge of the mountain passes (dervenagas) in Thessalia and Ipiros. The Sublime Port, appreciating his action, appointed him commander of Thessalia in 1787. The next year, he took advantage of the absence of the then pasha of Ioanina, Alizot. He conquers the town by deceit and manages to make himself recognized by the Sultan. He begins to establish and expand the areas under his occupation. He seemed to act in the interests of the Sultan, whereas in reality he was creating a state of his own.

Maybe he was a man of deceit if it was to achieve his goals; maybe he was one of the greatest and most savage tyrants the region had known; nevertheless, he managed to handle admirably certain social issues and transform the areas he was in charge of. Some of his positive work includes the elimination of quite a few “little” tyrants who made a fortune by bleeding their subjects white. He built many a school, bridges, water towers and he promoted commerce. He founded an Academy where many eminent figures taught. Great heroes of the Revolution graduated his military School. He attempted to make a regular army with European officials; he summoned chieftains, diplomats, important personalities of that time and initiated relations with Europe.

In 1819, he bought Parga (small scale sea city) from the Englishmen. Sultan Murat II seemed to worry considerably, both for his expansion movements and the meager taxes he paid. Comments on his way of acting begin and a year later the sultan declares him a traitor, he revokes his title, and summons him to the Sublime Port to explain himself within a period of forty days. That last part never happened. Thus, he assigns Ali’s annihilation to Ismail Pasobeis. The autumn of 1820, Pasobeis besieges Ioannina but he does not succeed in eliminating Ali.

Then, the Sultan orders the commander of Peloponnesus, Hursit pasha, who had a disciplined army, to go to Ioannina. [This would have a tremendous impact on the very first battles of 1821 revolution, since Peloponnesus occupying troops, were weakened.] He arrives in March, 1821. In November of the same year Ali’s first Turk-Albanians begin to surrender. Ali is left with less than 80 men. The state is dismantled and the army is disbanded. His children and grandchildren have been executed and their heads have been transferred to Constantinople. Ali had no choice but enter into negotiations with Hursit, who tried to deceit him by claiming he would intervene so that the Sultan would grant Ali amnesty. There was a truce, Ali retreated to the monastery of St Panteleimonas on the island of Ioannina.

On January 24, 1822, Hursit’s officials had a firman for death penalty, not for mercy. Hursit never showed up claiming he was unwell. In his place he sent Kiose-Mehmet pasha. When they arrived on the island, Kiose-Mehmet dlivered him the firman. The minute Ali read it, he knew. He shot him with his pistol. Then, Kaftan-agas, Hursit’s escort, tough warrior and chief of his staff, pulled out his sword to kill Ali. He missed but he wounded his arm. A few minutes later, he was shot dead by the bullets of the soldiers who holed up. They draw Ali inside and then a terrible fight follows. Hearing Ali’s groaning from upstairs, someone shoots him from the basement. He is wounded in the abdomen by a bullet. Thanasis Vagias disobeys his last order (to kill lady Vassiliki so as not to fall into the hands of his rivals). Besides, both of them were members of ‘Filiki Eteria’ (Association of Friends). Vagias calls out loud that they are giving in. They draw the wounded man out to the stairs where Meimet pasha beheads him.

St Kosmas’s prophesy has come true. Ali’s head was embalmed and taken to the Sultan. It was displayed for about a month and then it was buried along with the rest of his children and grandchildren’s heads in Constantinople. His body was buried on the inside of the Ioannina fortress together with that of his wife, Emine, who he had already had her kill. Lady Vassiliki and Thanassis Vagias went to Constantinople. They told the Sultan of Ali’s treasures in such a way that Hursit was incriminated.

(*) Some historians mention the date of 17/1/1822, as his execution date. The archbishop of Monastiri, father Ananias was exiled. Several months later, after he returned to the isle of Ioannina, he re-calculated the weeks that had gone by, reaching the conclusion that he had miscalculated by a week’s time, placing Ali’s death on the 17/1/1822 instead of 24/1/1822, which was the actual date.“

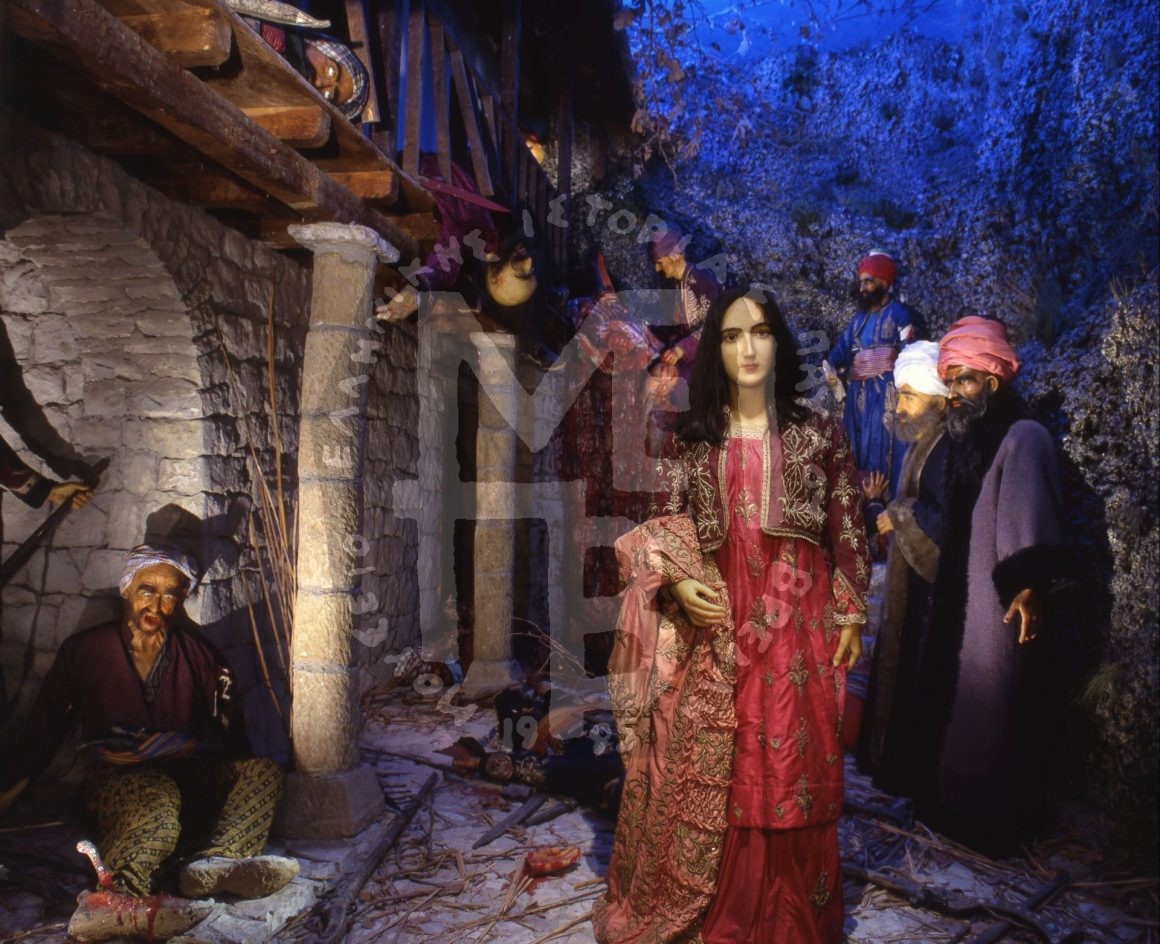

Description of Ali-Pashas’ slaughter

“The historical sources I had were plentiful. There were inconsistencies in some events too, some of which could be classified as descriptions while others as legends. I was greatly assisted by copper engravings, drawings, portraits and compositions of engravers and painters (both contemporaries and of later periods), as well as by books I had the pleasure to discover in collections and museums both in Greece and abroad (England, Italy, Germany, France).

I paid particular attention to the cells of Saint Panteleemonas. Since it was there those events took place, I took great care to depict the place. This project started at the end of 1976 and finished two years later. On present day, (2007), this place has been radically altered.

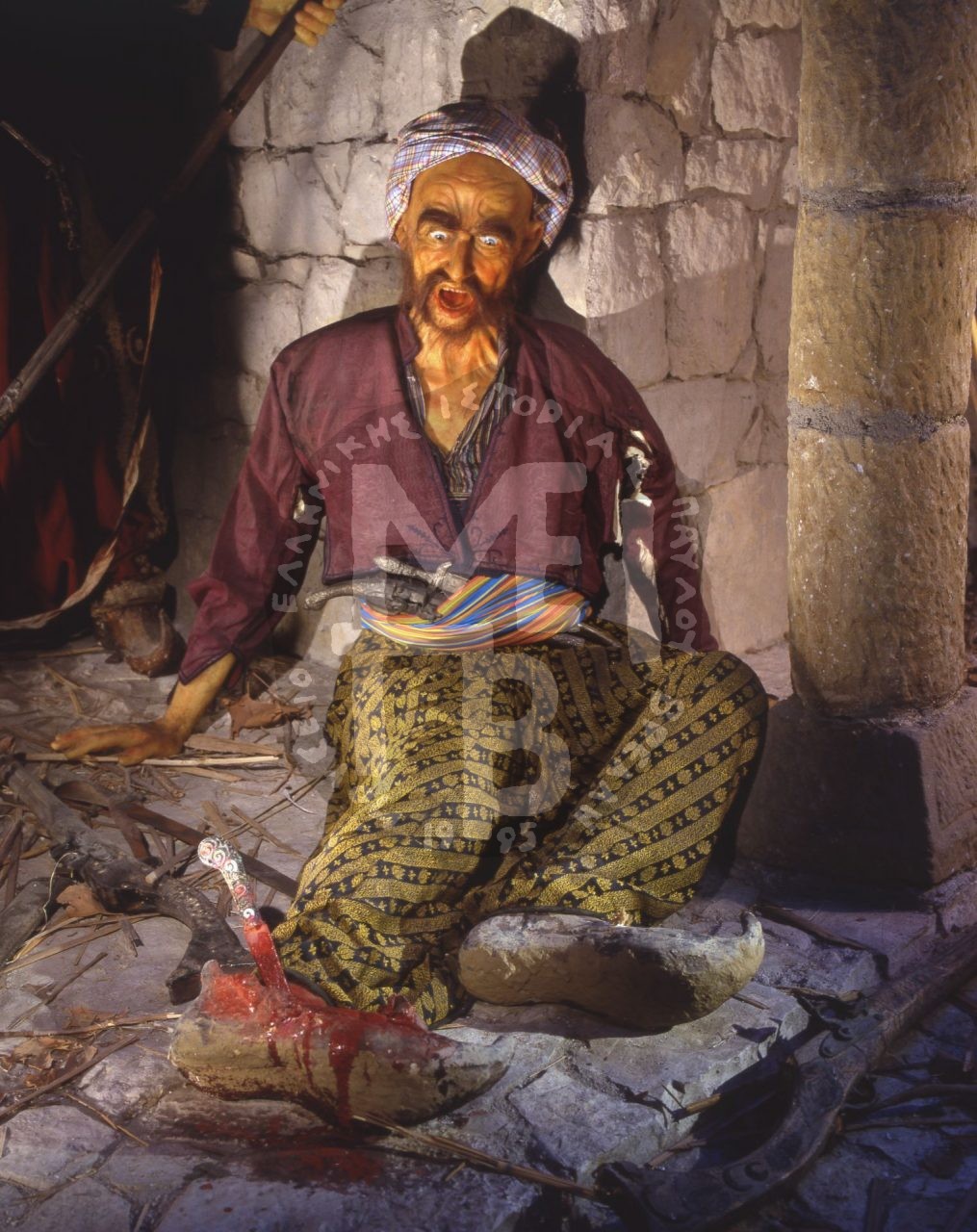

The twenty-person composition in this room is mine. The structure of the room is directly related with the reconstruction of the scene that unfolded. Ali’s bodyguard consisted of twelve Turk-Albanians. They are on the roof, behind the cave (only one of them is clearly distinguished), on the pillar-supported balcony and on the yard pavement. The ones alive are two; one behind the window (next to Thanassis Vagias standing up) and the other underneath the wall’s arch, on the ground floor.

The last Turk-Albanian, leaning against the wall corner, is stretching his wounded leg while his face shows sharp pain and horror. He is wounded with a knife stabbed in the tarsus bone of his right leg. As a result, we can see his facial muscles react accordingly and consistently. On the upper part of his face, we can see the metopic and the pyramoid along with other little muscles form the wrinkles on the face thus making his eyes appear open and wild passing on to us his pain and horror. The ultimate tension is apparent on the neck, with the muscular that keeps –along with other muscles up to three layers deep– his mouth open showing pain, an intense cry and anxiety which add to existing horror. This anxiety in particular is stressed even more by the tension of the muscles of the upper body.

I placed that figure at right angle, not only to portray in a tangible way a small part of the horror that resulted from such a slaughter, but most importantly to create a contrast to the serene and sweet figure of Kira-Vassiliki (lady Vassiliki), which on purpose I placed close to the visitor. She is the only creature who saved and helped people, the only creature who cared for others more than she has ever cared for herself.

In the background, on the ladder, lies Meimet pasha – Ali’s executioner. On his feet on the landing towards the corner, near the rocks, lies Kiose Mehmet pasha wounded on his left arm. In his right hand he is holding the firman with the written order to behead Ali. On his feet lies dead Kaftan-Aga, the first to be killed during the fight.

On their feet only for the sake of the composition, are a “Katis” with the white turban on his head, and next to him Omer Vrionis with the red turban. The latter was a Turk-Albanian and Ali Pasha’s right hand in many atrocities. Kati’s calm but stern face is fully opposed to that of Omer-Vrioni, a man of the same religion, yet so different in conduct and deeds.

I made their weapons with wood, pipes and ornaments. Some of these were made with fine brass plates on top of which I painted symbols and motifs with oxides. Others were made with ivory and rusty cast brass. Some of the woods for the making of the doors and windows are new. With before mentioned processes, I gave them the desirable patina, so as not to tell the difference with older ones. In that way, other elements (such as iron work), which I added right afterwards, were successfully embodied on the site. The conglomerate rocks on the left hand side of the composition were made from solid polystyrene, finely fluid gypsum and paint. They are sustained by a specially constructed frame of iron and wire. I gathered the reeds, leaves, branches and grass from the Ioannina island in February so that they have the same color as the season the event took place. I myself build the wall under the pillar-supported balcony, stone by stone. I drew the entire structure in such a way so that I could render back its natural scale with the help of certain details I tried to show off.

The clothes are bought from second hand shops. Most of them are from old half-worn uniforms. Kira Vassiliki’s outfit is a unique piece.”