The Interior

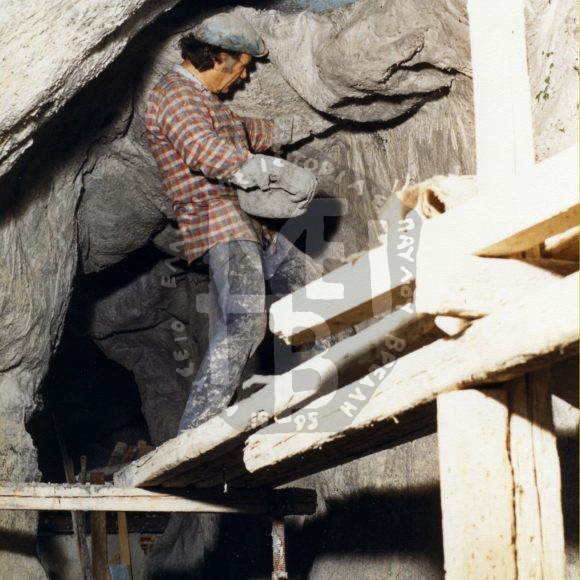

Let us watch the artist himself, on how he describes the forming of the interior of the Museum:

«In the midst of 1984, I began to separate the interior. I worked with the empty space the exterior walls of the building create. The dimensions of the façade are 23×12=276 square meters. There are three 40x40cm columns along the big, long axis. The height of the interior up the cement roof is ten meters. Therefore, there is an empty space of about 2,500 cubic meters in which I place my themes. This space is laid out according to the 36 theme rooms, which are incongruous and of unequal height.

In other words, the themes are developed functionally in the following ways:

- Parallel – Ali pasha’s slaughter on the first floor and Pavlos Melas on the ground floor.

- Subordinate – behind the rocks of the Ali pasha’s slaughter and above Ali Pasha’s head, the rocks of Pindos are being developed.

- Interrelated – part of Rupel’s pillbox, which is on the right hand side of the visitor, is seen in the composition of ‘the battle of Crete’.

I first took to outline my first theme with chalk on the ground: ‘the prisons’ being 2.5mt high up the way we got here. I placed some bricks on the borders and next I raised 2x1solid polystyrene surfaces all around as well as the corridor partitions. I followed the same procedure to all the rooms so as to see the bulk of the theme and its functionality at the same time.

It goes without saying that the preliminary work involved a number of drafts both perspective and axonometric ones, usually on a 1:25 scale. I made detailed and general scale models too.

I also studied the functionality related to the themes –not always in chronological order– as well as the space morphology. I took into consideration the effect the first theme might have on the rest. I built steady brick supporting walls as well as two pillars, and also at a distance of every meter and on all walls I built bind beams. Thus, with the help of these materials I interwove the themes on the ground floor. On top of these, I poured a slab of reinforced concrete, on different heights depending on the theme. I made passages and openings for these themes having them prepared though to connect them later on.

Then, I faced the walls with stone and painted the rooms according to the atmosphere of the theme. In the end, I placed the wax effigies in their predetermined positions.

The only composition which is one piece, down from the floor up to the cement roof, is the complex in openings composition of ‘Pindos’.

My benchmark is always the Man. I used harmonious speech according to the theme and occasion. In some themes, I increased the Order and reduced Complexity or vice versa so as to find the golden rule. In this way, I maintained unity in variety. I also respected the inner relation between matter and form as well as the one between form and content.

My main objective is to serve the visitor – viewer who walks touches and makes small and big steps down. I want them to move around at ease. You see, each visitor compares his body with the rooms, corridors, rocks, mountains etc. subjectively. This means they have quality as an external measure with which they draw the scale of the work they see by themselves. I maintain the reference measures to the human scale cautiously.

The objective space and the subjective one around us work together. The former is determined by measurable dimensions. The latter is perceived differently by each one of us. At this point I make the space bigger without changing its morphology. I am careful not to make the space out of scale or theme. For instance, the stones with which I have built the prison walls on the inside and outside look larger in comparison to the small ones high up the room or down on the floor.

As you have read in my introduction, the interior of the museum is constructed in such a way that it functions as a museum only, for these particular themes.

The twelve years of work is quite a lot of time, as I got started at the age of 60 and faced many difficulties such as weather conditions, financial problems, artistic consciousness –artistry and perfectionism– which led me to this point.

“A piece of work like this never ends. I feel I stopped at the right point. “

What I did, as a historical and artistic education is a contribution, even a small one, to my home country. It is the past, and without the past there is no love for the History of this place.»

Pavlos Vrellis, a sculptor

Bizani, Ioannina, winter of 1994/5