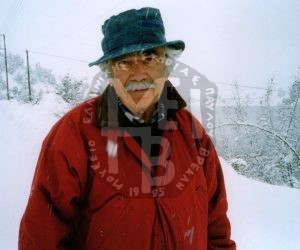

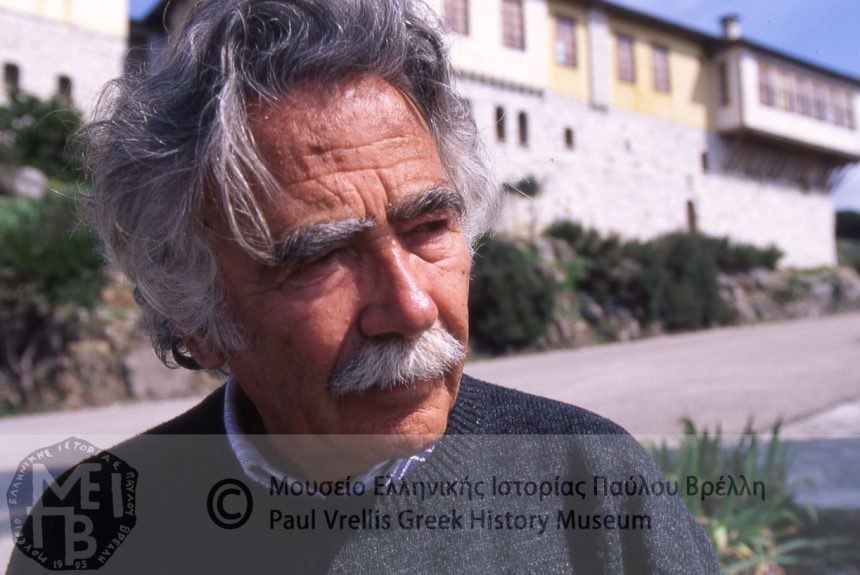

Pavlos Vrellis

Born in Ioannina on March 25, 1923, he was left motherless at the age of 4. Nine years later, he lost his father as well. His aunt, Sophia Paramithioti, his mother’s sister, raised him and educated him. Her role both as a pedagogue –a teacher herself– and as a presence of great artistic education influenced him deeply.

Her task was tough. Not only because the First World War left intense scars behind it, but because Pavlos was the most lively of her nephews. His artistic nature had already begun to show from his early childhood, when he drew and carved on wood or stone his favorite heroes. His other side was the one that made him move forward and go ahead, though. His lively nature and his love for action and discoveries kept him mentally alert when, as a teenager, he got arrested by the Germans during the Occupation; along with other children they would clean the remains of war material that had not been exploded.

Having lived as a man about to die, while in prison, he would carve ordinary things on wood waiting for his last moments; he witnessed friends lost for good and copied the forms of his fellow prisoners with a different insight. He began to experience his first spiritual anxieties, which were now based not on an impulse for exploration, but on a need to express through his feelings what touched him more.

Following his aunt’s wish and urging, he got into Zossimea Pedagogic Academy in 1945 from which he graduated in 1947.

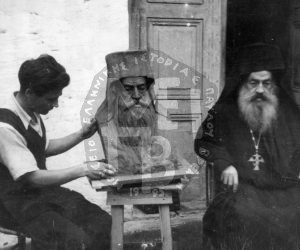

When he was 23 –before he got to the School of Fine Arts– he took to making busts. Busts of G. Kaloudis, G. Lytras, and General Reppas precede that of Metropolitan Bishop and later Archbishop, Spyridonas Vlahos. That work of his marked not only its course but mainly its end. Praising him for the bust he had made, Vlahos offered him not a negligible sum of money as a fee. Vrellis refused to take the money saying: ‘I do not wish to start my career with money’.

For this reason, he gained little experience in busts, with the little knowledge of anatomy, osteology he made part of himself painstakingly. It was then he got engaged in carving, mainly on upright and oblique wood, using tools he made himself. Some of his work of linoleum technique was published on local newspapers of the time.

His keen observation and love for this subject, as well as his faith in art and life were his driving forces. Thus, pursuing his dream, he got into the School of Fine Arts in 1949. Unfortunately, his military service during the civil war left him psychological scars; what is more, the whole course of his career, which he painstakingly had started to pursue, fell behind.

As an artist-creator he begins to explore various paths. With clay and patinas of his own, he creates fruit almost identical to natural ones; he sketches whatever seems intriguing and tests himself in painting and carving, receiving laudatory reviews on part of professors who wanted to keep him in their classes.

After doing his military service, he went on with his studies and at the same time he exercised at Fokianos Gym and participated in games, gaining distinctions as a pole vault athlete – ‘Aktia’ 1950 and ‘Dodonea’ 1950. His quest did not end at the art he chose and the sports he loved; he also attended classes of Byzantine music and took elocution lessons.

Some of these activities had to be broken up as the classes at the school of Fine Arts became more and more demanding. Later on, he would admit this break was to the best as it enabled him to perfect his Art.

He was taught artistic anatomy by Apostolakis –on corpses just like medicine students did, and according to him, this knowledge became the ‘correct spelling’ of his work. He was taught History of Art by Pantelis Prevelakis, who told him of the proposal by the eminent English sculptor Henry Moore to be his supervisor. His response was that since ‘nothing can grow beneath a big tree’, he wished to be an autonomous unit and he himself be a reference point with his work.

In the field of sculpture, Michael Tombros was his professor. In fact, he called him the best portrait student he ever had. If only several other people (mainly from his homeland–Epirus) whose busts he sculpted, would share the same opinion. Not only did they not pay his labor; they did not even pay for the materials and foundries either. Maybe he was too realistic in life and his art, thus any pretentious narcissism had no place in his creations.

In 1954, he graduated having both a Theoretical and a Practical Degree. He is now the first student from Epirus who entered the school and graduated from it with such qualifications.

His studies did not stop there. He got a scholarship and attended lessons of Copper Sculpture Art and Technique in Florence, where he worked for a short period of time, and Tessellation in Ravenna.

His love for sculpture and painting always urged him to seek ways of making it superior. Either way, he always believed that better is the “enemy” of good. The harmonious engravings and cyber science, both as a theory and as a way of viewing practical applications, was the heart of his parallel study for years. He also tried to keep up with the developments of his time. He often traveled abroad and attended new exhibitions or visited museums whose exhibits he considered important.

One of his most significant experiences was the preservation of parts of the Museum of Acropolis, assignment which particularly honored him and still touches him. After that, he worked at the Archaeological Museum for three years. During that time he obtained two recognized patents which enabled him to materialize the foundation of the Reproduction Department of Classical Antiquities. He recommended the creation of this department himself and he was also in charge of bringing it into existence.

He worried about the educational system, which drove him to work out and recommend a curriculum applying a certain pedagogic method. This was first applied to Tzanio Experimental High School in Piraeus, where he taught successfully for years. Indicative of his presence was the fact he took his students on tours to Archaeological sites (the Acropolis, the Archaeological Museum, Keramikos) since he regarded them as an organic and integral part of education. As a guide tour, he traveled to and enjoyed places like Ancient Olympia, Delphi, Mistras, Constantinople, Ancient Dodoni, the Nikopolis’ oracle of the dead, the monasteries on the island of Ioannina etc

He got married to his for long time sweetheart, Maria Giannisi in 1962 so he transferred his activities to his homeland. The life of a sculptor in the country was tougher than he thought. Quite a few pieces of his work may be encountered today throughout Epirus, but these are mainly busts or war memorials. The creations of a man engaging in work of pioneer conception and contemporary character cannot “thrive” in the climate of Epirus! Nevertheless, he kept on taking part in group sculpture exhibitions in Greece. He also toured around Epirus and gave lectures, while, at the same time, he studied closely Epirus Folk Art, like he had done in the past.

He worked mainly as a teacher of Art and Craft in High schools. He became aware of the flaws of the educational system and along with his lessons he prepared prospective candidates for Architecture. Since there were no such courses for candidates for the School of Fine Arts, he set up his own School, which he kept for several years, providing the necessary qualifications not only teaching line drawing and freehand sketch, but also with his overall artistic education. He obtained two children, Constantine in 1966 and Ann in 1970.

He was attached to the University of Ioannina for 7 years to teach History of Art and more specifically current artistic trends. Through several acquaintances with other professors, he dared provoke certain people in favor only of the theoretical approach of the lessons. He displayed exceptional sensitivity on the subject of History in particular, since he regarded it alive always within all and indispensable for all.

In 1975, as a part of an experiment helping the teacher to present, in a unique way, the historic topic he wishes, he chose to display the first theme he created ‘the Clandestine School’. He transformed a place where the visitor could be part of it, and therefore, part of the history being represented. He gave the place life by creating human forms made of wax, forms playing the role of the protagonists. The work of a sculptor of classical education had preceded; a sculptor working first with clay, creating a mould of plaster and finally casting the wax. By means of all his qualifications he had gained so far (both mental and material), his work was complete. This work first excited the circle of people for whom it was destined to, and later the whole Greece –around 8 million people visited that Museum.

He continued to write poetry, something he did since he was very young, but because he was a hard judge of himself, he never published anything. The first three books of this period are: ‘Recollections’ /1969, ‘Forms’ /1972, and ‘Irons, Stones and Flowers’ /1975.

By 1981, he had added more themes-rooms. He has many more on his mind, but they would not fit in such a small place.

He wrote two more collections of poems: ‘it Was and it Is’ & ‘Iron plates and Outlaws’ / both 1982. Having retired with the rank of principal of junior high school, he decided to exclusively engage in his work.

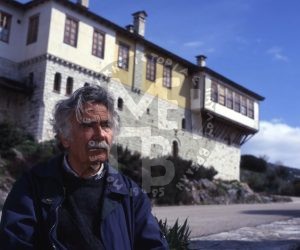

In 1983, 60 years old at the time, he bought with the retirement payment a 4-acre land in Bizani village. He traced roads and squares; he made the exterior place in such a way so that it wouldn’t be ‘visual pollution’ to the environment. He planted numerous trees. Finally, the building which would accommodate the museum was given the style of the urban fort architecture of Epirus mainland of the 18th century, absolute respect to tradition being paid.

He divides the building itself into levels [parallel, synallel (having one side common) and diallel (the one runs through the other)], creating, thus, an utterly extraordinary place. Disengaged from the usual display rooms, he set up various scenes in the interior which would host his wax models; all of them related to the Greek history. In this difficult task, he had old friends and students by his side, as well as the Association ‘Friends of Pavlos Vrellis’ Museum’. The state’s contribution was also significant when Melina Merkouri, Minister of Culture, and Alexander Papadopoulos, Minister of Finance helped him out at the finishing touches, both morally and financially.

This museum began to receive visitors on July 31, 1995; the complementary comments he has been receiving for his work, do him justice for the so many years of manual and mental work. He believes that ‘Rich is not the wealthy one but the giving one. I am rich myself, for I managed to offer Greeks this piece of work’.

On July 23, 2010, he passed away.

Pavlos Vrellis has participated in the following group exhibitions:

- Gallery of Art (Athens, 1960, with sketches and sculpture)

- 6th Pan-Hellenic Exhibition (Athens, 1960, with sketches and sculpture)

- Epirus Exhibition of Folk Art (Ioannina, 1962, with drawings applicable to folk Art)

- 1st Two-year Sculpture Exhibition (Athens-Filothei, 1966, with two sculptural compositions)

- 4th Exhibition of Graduates of the School of Fine Arts (Athens, 1966, with painting)

- 11th Pan-Hellenic Exhibition (Athens, 1971, with bronze sculpture)

- VIIIme Grand Prix International d’ Art Contemporain, de la Principaute de Monaco (1972, with a sculptural bronze composition and a silver figure)

- 12th Pan-Hellenic Exhibition (Athens, 1973, with kinetic sculpture and bronze composition)

- 13th Pan-Hellenic Exhibition (Athens, 1975, with kinetic bronze sculpture)

- An individual exhibition in King’s Gallery, (London, 1972, with kinetic sculpture, silver and bronze figures, and sketches)

**

He has been awarded for his work by the following:

- Greek Confederation of Epirus (1981)

- Historic and Ethnological Company of Greece (1982)

- Association of Nature Lovers of Patra (1984)

- Metropolis of Patra (1984)

- Local Federation of Municipalities (1991)

- Municipality of Ioannina (1992)

- ‘Saint George’ Society of Ioannina residents (1992)

- The Rotary Club of Ioannina (1993)

- VIII Division (1993)

- Association of Development of Ioannina Unity (1993)

- Teachers Association of the municipality of Ioannina (1996)

- Federation of Police officers of Epirus (2000)

- Federation of Bank Personnel of Greece (2001)

- Colleges of Arta (2001)

- Air Force –accompanied by a relief of 5,000€ to the museum (2004)

- Epirus Association of Litterateurs and Writers (2008)

Konstantinos Vrellis, August 2012